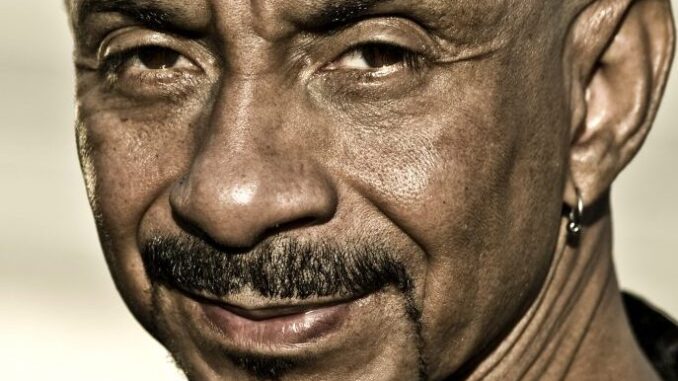

Ty Granderson Jones puts all his might into acting. He’s a protégé of the iconic theater director Alan Schneider and studied under acclaimed acting teacher Lee Strasberg. He has an MFA from the University of California San Diego, one of the world’s top drama schools. Having played his share of pimps and gangbangers, the street-tough actor has resisted being typecast in roles that focus on his short stature and Cuban-Creole heritage.

Early in his career, Granderson Jones caught the eye of Oliver Stone, who cast him in his Oscar-nominated war film “Salvador.” Relying on his training, the ambitious actor fully embraced roles in cult classics like the prison comedy “CB4,” featuring Chris Rock, Charlie Murphy and Allen Payne, and “Harlem Nights,” which starred Richard Pryor, Eddie Murphy, Della Reese and Redd Foxx. He was featured in the box office hit “Con Air,” an action thriller starring Nicholas Cage and John Cusack.

He has scored roles on the TV shows “ER,” “Everybody Hates Chris” and “Webster.” He wrote, produced, directed and co-starred in the award-winning thriller “Diamond.” Granderson Jones is also an internationally recognized acting coach. Having worked professionally since the early ’80s, Granderson Jones credits his longevity to his theater beginnings. A known badass, Granderson Jones is versed in Muay Thai, boxing and wrestling.

He talked with Zenger News about his artistic aspirations, his conflicts in the movie industry, and the uneasy fun of hanging out with Richard Pryor.

Percy Crawford interviewed Ty Granderson Jones for Zenger News.

Zenger News: I used to see you in all these tough-guy roles, and I felt that had to stem from your past somehow. You were always cast in roles of being this hardened tough guy.

Ty Granderson Jones: [Laughing] It didn’t start out like that. I come from the theater. In my opinion, and I’m a bit biased, I think the most magnificent actors come from the theater. I turned my life around after being locked up for almost two years. I can’t even really talk about it, but it was swept under the rug. Maybe I shouldn’t say that. But honestly, no … I’ll say it, because I won’t be the first — and I’m sure I won’t be the last — to get a second chance because his family had connections or money. You just don’t hear that story when it comes to men and women of color. You always hear about the little white boys and white girls that got the second chance.

My father; I lost him in 2014, my hero, man. He brought home Julian Bond, Shirley Chisholm, Barbara Jordan for dinner. He was a political activist that changed a lot of people’s minds and lives. I don’t know how I got under that, but when I got to Hollywood, when I turned my life around and got into theater. I’m from the streets, but I’m not the little bad guy, the criminal and the convict anymore who was dealing contraband and getting in gun fights. Miami Beach — which they call South Beach now — we making deals coming out of high school up in the penthouse of the Marco Polo Hotel in Miami.

My father had kicked me out of the house at 16. So it was like, what do I do? My junior and senior year, I had my own apartment and was doing some other things. But the point I’m making is, it wasn’t all about Hollywood embracing me to play the little bad guy. That’s something I marketed, but I thought I would be able to do what they were trying to push on me, which was to be the little funny guy. That was so not interesting to me. Especially given where I had come from. There were two guys in my neighborhood coming up, me and another kid about my size, and we’re 5 [feet] 4 [inches]. I lie to this day and say I’m 5’7, because I look big on film. When my wife finally met me, she said, “I thought you were taller.” But I ruled my neighborhood. I was a beast. But the other little tough guy — his name was Bobby.

I remember his name to this day. We would see each other coming down the street, and we would cross the street and try to get away from each other as far as we could, because neither one of us wanted any part of each other. We were two little guys running the neighborhood. It started in junior high where the big threatening bully fullback would skip people at lunch, and one day he skipped me and I slapped him like a little girl, and he couldn’t believe it. Then he got his cousin, and I had brass knuckles and I knocked his cousin out — he didn’t see them brass knuckles coming — and I got suspended.

Zenger: I read where you said they [studios] were trying to make you Kevin Hart before Kevin Hart. The short, funny guy. And you had no interest in that at all.

Granderson Jones: My first agent told me, “I don’t really see much for you. I don’t see you playing anything more than maybe George Jefferson’s little brother.” That was an insult. Nonetheless, the industry itself was trying to push the sitcom stuff on me. They wanted me to be the little funny guy. I was Webster’s music teacher, Lorenzo; I recurred on that. I was doing a good job with the sitcom thing because I come from theater, with the audience, so it was a piece of cake.

Zenger: Do you remember your movie break?

Granderson Jones: I starred in a movie. Me and Bill Pullman. I starred in a movie called “Dive.” And we changed the title to “Going Under,” and that’s exactly what the film did [laughing] — it went under. And I’m glad to this day. I made a really nice script, but it was the silliest film, starring Bill Pullman, myself and old-school Robert Vaughn and Ned Beatty. It was my first big starring film. It was a Warner Brothers film. It was a spoofy, funny thing, and I’m funny as hell in it. Then I did [TV sitcom] “227” and all these things, and I’m saying, “You know, this is not me.” Number one, I don’t like being taken advantage of because of my stature. That was part of the chip that I had on my shoulder that got me in trouble in the first place … because it’s not like now. Michael B. Jordan and a lot of these guys, in my humble opinion, are taking advantage of what the generation of actors that came before me and my generation paved. I’m an ‘80s-’90s guy when I got here. There wasn’t a lot of work like there is now for actors of color. But I didn’t come to Hollywood to be this guy.

Zenger: Did you ever think about quitting and going in another direction?

Granderson Jones: No, never wanted to give up. I wanted to make a valiant effort to try and market myself and my craft and my career like a couple of these white boys, like Tim Roth, Gary Oldman and Joe Pesci. We’ve never seen that. All my boys say, “You know what, we ain’t never seen no black Latin Joe Pesci.” That’s what I was attracted to. That’s what I was going after. That’s the school I came from working with, [Lee] Strasberg and those guys. I come from the school of [Robert] De Niro and [Sidney] Poitier. That’s the career I was looking for. Although, I never knew I would get here. Many are called and few are chosen. God chose me to do what I’m doing, and it was like divine intervention in so many different ways that got me here.

Zenger: Your role as 40 Dog in the movie “CB4” — you nailed that role, but you weren’t interested in even doing it, correct?

Granderson Jones: No, I didn’t want to do it at all, man. First of all, I didn’t know about it. I didn’t have an agent. I was at a coffee shop one night, and this guy — white guy, dynamite actor. He was there. He was with the same agency that I used to be with. I told him that I wasn’t with that agency anymore, and he introduced me to his girlfriend, who was an African American. And she was an agent. She said, “Have you read for 40 Dog, for “CB4,” yet?” I didn’t know what she was talking about. I told her I was in between agents. I didn’t have an agent at the time. She said, “I’m going to submit you on Monday.” She submitted me and nothing came about it. And then I heard a lot of rumors from Hollywood that the casting director knew of me but wasn’t sold that I was the right guy for the role.

See, the role was originally written for Too $hort. That’s what I heard. For some reason, it didn’t work out. But I heard Chris Rock wanted Too $hort. They wanted a short, edgy guy like that. I didn’t see myself as that, but they couldn’t find the right guy, so it opened up to a guy that looks like me and who was edgy. They kept calling around and everyone kept saying, Ty Granderson Jones. Nobody really wanted me, but finally my name kept coming up and they brought me in. I had to read with Charlie Murphy for Chris Rock and Tamra Davis, the director. I had done “Harlem Nights” already and hung out socially with Charlie. We had a little chemistry. We read and it was magic, and I was hired on the spot.

Zenger: Initially, why didn’t you like it?

Granderson Jones: When I initially read the script, it was like, “Okay, more shit taking advantage of me being short. It had nothing to do with craft. Another spoofy little comedy thing. I always wanted to do Oscar-caliber material. I didn’t know my height and my look… I’m not traditionally African American looking. I didn’t fit the stereotype of any bracket. I didn’t take any of that into consideration. I didn’t understand it was a business, and they look for a type.

I remember the first day of showing up on “CB4” and Charlie didn’t know his lines that well. We weren’t that close, but I got a master’s in fine arts in acting from the third-largest program in the world. If I’m going to do the spoofy thing, then I’m going to take it very serious. My approach to 40 Dog was like a very serious role: Don’t play the comedy of it; go and play the drama of this role. And take this whole project seriously. Charlie said he didn’t know his lines very well, and at the end of the day, I told Charlie two things: “You know, guys are basically going to say you got this role because you’re Eddie’s brother. You’re Charlie Murphy.” He goes, “What? Wow, OK, yeah!” I said, “This is your time to rock, this ‘Gusto’ role, bruh.” That was number one. I said, “Number two, I’m taking this shit very seriously. You’re in a scene with me.” I remember Chris [Rock] saying, ”Oh, you’re one of them serious actors that prepare.” I remember Chris making jokes about me when we were in scenes together because I’m quiet and focused and thinking about my next line. I’m not messing around. Chris was a comedian, Charlie hadn’t done much, and he’s funny as hell. His brother was the biggest comedian in the world. They weren’t taking it serious the way I was taking it serious. Not saying that their work didn’t pan out — obviously, it did — but if you look at the film, my influence on Charlie’s approach in the scene was very serious, where everybody else is playing the comedy.

Zenger: Where did the voice box come in? Who came up with that idea for you to have a voice box?

Granderson Jones: That’s the way it was written, but if you go back and look you can see that they didn’t do it right. They didn’t have it in the budget, for whatever reason. There should have been a hole in my neck or some type of wound in my neck. Was 40 Dog born that way? These are things that should have been asked. See, when I go to work, even back then with “CB4,” to prepare for a role, there are questions to be asked and answered. The who, where, what, when and how’s. This is something that I teach my students when I coach. Who is this guy, and how did he get that way? They should have been able to do it in pulse with sound effects. But again, either they weren’t aware of technology or they didn’t have it in the budget. I can’t tell you what that is to this day.

But what I can tell you is that I got into some beef with Universal Studios. I don’t think [“CB4″ producer] Nelson George likes me to this day. I’ll run into Nelson George at Target and he acts like I’m a complete stranger. And the only thing that I can relate to is, when they couldn’t figure out the right vibe for the voice of 40 Dog, Chris, in his arrogance at the time, was like, “Let me try something, and I can do Ty’s voice.” And I was like, “Number one, I didn’t want to do the shit, and number two, now you’re talking about coming in and have Chris dub my voice because y’all don’t have the budget, so he can make some shit up. It’s not happening.” So, I brought in my lawyers and things. So I did a “Fuck them bitches,” in that voice, and I have never said this publicly, but you can tell there is a little bit of Chris’ voice up under that. I never made a big beef about it. I was at the premiere sitting with Angie Basset and everyone else I know in Hollywood, and I said, “Yeah, that’s me, but something… let it go.” Next!

Zenger: I am a huge Red Foxx fan. I read where you said he didn’t like you on the set of “Harlem Nights.” What was going on with you and Redd?

Granderson Jones: No, he didn’t. You have to understand, though, let’s look at where Redd Foxx was at the time: His health was an issue, his health was in jeopardy, he had lost everything. The IRS had taken everything from him. He was older, not healthy, therefore a step slower, and you got this little young blood on there eating his ass up when he hears “Action!” But I went in to read for Eddie. I read for the ”Crying Man” part that Arsenio [Hall] did. That’s what it was called, “the Crying Man” — something like that. I went in there and I tore that shit up, man. I can relate because I was that guy when I was really low getting my ass whipped, I pick up a brick and be crying, “I will fuck you up, man.” I knew that guy well because that was me. At the time, I didn’t know that that was a role that he had wanted his boy Arsenio for. The way I heard it, at the last minute, Eddie and Arsenio make up and Arsenio ends up doing the role. SAG [Screen Actors Guild] unions, once they negotiate a contract, they gotta pay you, so I had 10 grand coming to me for six days anyways. Today it’s not a lot of money for that, but back then, “Yeah, I’ll do this for a week for 10 grand.”

I didn’t really know what they wanted me for until I showed up on the set. Something great happens. Eddie comes up to me and he goes, “Look, man, I don’t know what we’re going to do here. I know there’s this role here where we can put you at the crap table. It’s in the script. We will call you, ‘L’il Gangsta,’ ‘Casino Man,’ something, and we’re going to do a whole bunch of improvisation stuff.” When we started rolling with Redd Foxx, it was just improvisations. There wasn’t much of anything in the script. What I said wasn’t even in the script. “Hey, man, that’s an eight or a nine,” or something like that. I excelled in improvisations. So, Redd says — which was in the script — “I’m sorry, I got something in my eye.” That’s when I go, “Well, get it the fuck out yo eye, you blind motherfucker.” Redd was starting to feel insufficient, like he couldn’t keep up. I wasn’t looking at it that way, until I realized he wasn’t feeling me. When he said, “I ain’t gonna be too many more motherfuckers,” that was serious. That wasn’t in the script. But afterwards, I went up to him and I said, “Hey man, I was just doing my job. My uncle [jazz trumpeter] Nat Adderly told me to tell you, ‘What’s up?’” And he said, “Oh man, I was on the road and opened with them back in the day.”

Zenger: A lot of talent on that set of “Harlem Nights” who are no longer here with us. I’m sure they all have a special place in your heart.

Granderson Jones: I had already met Richard Pryor and spend intimate time with him. I didn’t get to really talk to him on the set of “Harlem Nights,” because when Richard is focused, he don’t like anybody to really mess with him or talk to him on the set. But the way I knew Richard fairly well, one of my mentors is an actor by the name of Art Evans. When Art was doing “Jo Jo Dancer” with Richard Pryor, he called me up one day and told me he was going to pick me up in his new Porsche. These guys are older than me by some years. I wanted to go hang with them to learn something. He said he was about go to the set to go hang out with Richard Pryor, and asked if I wanted to come. Well… fuck, yeah! It’s just me, Art and Richard Pryor in his trailer. Richard had a big bowl of fruit, and he goes, “Have some fruit.” I grabbed some fruit, him and Art talking and laughing, and I grabbed another piece of fruit, and he says, “Motherfucker, I said eat some fruit, I didn’t say eat up all my motherfucking fruit.” And I looked at him and I put the shit back, and he said, “Man, I’m fucking with you.”

(Edited by Jameson O’Neal and Alex Patrick)

The post Ty Granderson Jones Strives To Act Above His Weight Class appeared first on Zenger News.