By Beverly Dawn Whatley, M.Ed.

“Keep both hands on the wheel”. “Don’t make any fast moves.” “Ask and reach slowly for your ID.” “Answer.” “When you can, put your hands up.” “Don’t fight or run.” “Live another day.”

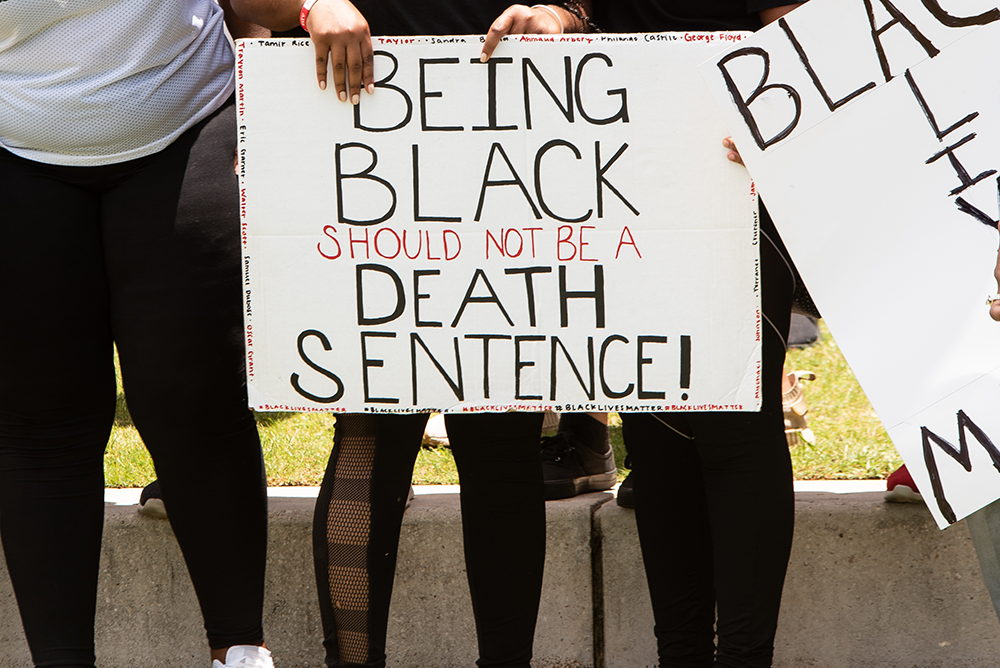

Lines from a movie? No, survival tips given to young, maturing Blacks, especially males. Despite being 13% of the population, Blacks are: 21% of police contact; 33% of the incarcerated; and three times more likely to be killed by police than Whites.

We’ve always considered there was a presumption about Socio-Economic Status (SES) and race during an encounter.

What was the stuff of legend and rumor is now documented on video. Doorbell surveillance, security cameras, body-cam footage, and citizens with cell phones are at-the-ready 24/7. There are guns and badges on our streets that are not ready to wear the uniform. Fortunately, most cities are blessed with a larger percentage of officers dedicated to “protect and to serve”.

What can be done to retain the law, yet take some of the “force” from law enforcement?

Not all on duty are fit for duty…

Unfortunately, there are those drawn to the force with the same heart as the

“patty-rollers” of the 19th century. These were the slave patrols who rolled around the backroads as slave catchers. They were sworn to hunt down and return runaways, but also to sniff out any weapons that might be used in an uprising. Runaways, free-men-of-color, or those with papers in order were all subjected to cruelty. The color of your skin was enough to make you suspect. Excessive force was enough to make you compliant.

The 13th Amendment may have ended the practice on paper, but not in spirit. The militia style groups assembled to “protect” by enforcing [anti] Black Codes, were armed, fueled by their official and unofficial oaths, and trained only to intimidate and kill. The theory was to protect all entitlements that came with being White from being infiltrated by and shared with Blacks. The best known and organized was the Ku Klux Klan. The white hooded garments disguised their identities, but the look was also a tribute to fallen Confederate soldiers. These “ghosts” marched through towns striking fear and obedience in the hearts of Black folk. Every family knew of someone who had been lynched or made to disappear. The numbers of such radicalized groups have ebbed and flowed, but attitudes remain strong.

The 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868 to end the Black Codes, but systemic excessive force in conjunction with discrimination had deep roots. Like a vine one can’t kill, it spread. In flies, “Jim Crow” and a series of laws and policies that reminded post-Civil War Blacks, you may be emancipated, the Codes may be gone, but you still ain’t free. That bird dropped its toxic load from North to South until the 1960’s. The fight for Civil Rights is ongoing.

Not just a Black and White issue

Around the United States police agencies have long formed task forces in response to need. Whether due to guns, riots, high crime, or dangerous drivers, each internal unit was crafted “on paper” to address an issue and restore order for that city. Blue uniforms on Black bodies have also racked up an alarming number of Black deaths. Out of respect for the families their names will not be mentioned.

In 1966, after being overwhelmed by snipers during the Watts riots, Los Angeles police chief Daryl Gates formed the first Special Weapons Attack Team (SWAT). It was composed of ex-military police who trained with the Marines. Many in the department didn’t get behind their tactics. However, in 1969, when serving a search warrant for illegal weapons on Black Panther Headquarters, a shootout with heavily armed Panthers ensued. After four hours, thousands of rounds, and three injuries sustained on each side, the Panthers surrendered, and SWAT’s position was secured.

In 1971, the Detroit Police Department established the Stop the Robberies and Enjoy Safe Streets unit (STRESS). It only lasted a few tumultuous years when it was disbanded by Mayor Coleman Young in 1974. The Black community was targeted by use of excessive force, with dozens shot or wounded. Twenty-two people were killed by the unit, most being young, Black males—most of them unarmed.

In 2021, the Memphis Police Department launched a crime-fighting unit. Street Crimes Operation to Restore Peace in Our Neighborhoods (SCORPION). It was made up of forty officers in four teams assigned to identified high-crime areas. Chief C.J. Davis planned to address reckless driving. Writing tickets wasn’t enough. Some offenders would also lose their vehicles. At a forum the Chief Davis expressed additional concern about gun violence. A recent disturbing video documented excessive force leading to the death of a young Black man. The officers were charged with murder. This unit was permanently deactivated January 28, 2023.

Early Attempts at Correction

Social justice historians can review the Wickersham Commission, the first in the U.S. to study law enforcement, including police procedures in May 1929. Then the Knapp Commission, April 1970, to learn known problems existed, reform was needed, yet a code of silence was thickening the line. H.R. 7137 introduced in June 2020 addressed use of force especially in communities of color. The word “defunding” was not used but the narrative to prohibit receipt of funds…by units that failed to adopt minimum standards made limiting access to revenue a point.

Police Reform

The video of a man dying under the knee of an officer sickened the world, and resulted in the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act of 2021 which passed the House March 3, 2021. This bill addresses policies and issues:

- Accountability for law enforcement misconduct, creating a national registry to compile data on complaints

- Refreshed reporting requirements for recording use of force and routine policing practices (ex. stops and searches)

- Restricted use of certain policing practices

- Transparency with data collection

- Training requirements with established best practices

- Requirements that officers complete coursework in racial profiling, implicit bias, and intervention when a fellow officer exhibits excessive force

- Department of Justice (DOJ) cooperation in establishing uniform accreditation standards for law enforcement agencies

Additional framework seeks to restrict no-knock warrants and any forms of the chokehold. It also pursues ways to prevent racial profiling at the federal, state, and local levels. If an officer is charged, the criminal intent standard would change from “willful” to “knowing or reckless” to convict misconduct in a federal prosecution; qualified immunity as a defense would be limited; and the DOJ would have subpoena power to conduct investigations. Now, the stalled bill needs to pass in the Senate.

So, what does change look like?

Reform doesn’t require a federal mandate. Changes are happening at the state and local levels. At least 30 states have enacted their own legislative policing reforms. Many states have changed their standards for use of force, now calling deadly force a last resort.

City response includes recruitment of more officers; funds invested for better housing and violence prevention; creation of crisis response teams for the behavioral calls; and a reduction of police presence in schools. This pays off with fewer arrests, better community relations, and economic savings.

Moving forward…

The most impactful need for law enforcement is not to defund but to retrain and acquaint the police force with the community they will serve. This is imperative when the demographic does not look or live like the officer. It is easy to “other” a population as less than human when you can ignore their humanity. It might not always be feasible that the officer resides in the same zip code, but he/she can know the territory. Who are the people? What are their norms and traditions? What do they value? Who do they look up to? What do they want for their families and their communities? With just knowing the answer to these and related questions, that thick, blue line between us and them may thin.

Our communities need to properly select and serve only those who will bring honor when they suit up in rural towns or big cities. The sight of a patrol car should only elevate blood pressure about a ticket or a taillight. It should not feel like it might be the end.

Black children should be more familiar with “Officer Friendly” visiting their school and touring the squad car as a tool of community service, not an inevitable conveyance. When asked about future career plans, we might again hear, I want to be a firefighter; I want to be a teacher; I want to be a police officer. If we can get to that point, our future will be in good hands.

About the writer

Beverly Dawn Whatley is an alumna of Eastern Michigan University and Chapman University of Orange, CA. As an educator Beverly, a former secondary and college instructor, is a literacy specialist and instructional coach for the state of Michigan. She is a member of the actors’ unions, allowing her to work on film, television, stage, and nightclub projects. Due to her work in documentary production and TV news, a keen journalistic inquisitiveness inspires her writing. Fueled by a strong sense of Black activism, Ms. Whatley has tackled courageous topics published in B.L.A.C. magazine of Detroit, and regularly contributes to Heart and Soul. She has written for The Crisis of the NAACP. When time allows, Beverly seeks more voice-over work.